Arctic Wednesdays 2023: Week 1 Post-trip Blog

Eliza Braunstein

Title I Teacher

Conway Elementary School

We can see the summit of Mount Washington from our elementary school playground. On

early autumn days, its rocky summit stands tall - 6,288 feet tall - against sunny, blue skies. On

winter days, its snowy slopes are stark white whenever it appears from the clouds. Today, as I

write this blog, it was enshrouded by the fog that surrounds it two-thirds of the year.

This well-known peak drew my interest from the first moment I traded in my life as a

professional mariner on the high seas - where I lived and breathed weather in every moment - for

life as a schoolteacher at Conway Elementary, which is nestled in a valley defined by the

mountain that rises above it.

I soon applied to Mount Washington Observatory’s Arctic Wednesdays program, eager

for the chance to explore the “home of the world’s worst weather” and to connect with my young

students from the summit. I was scheduled to make the trip on March 11th, 2020. Two days before

our departure, I received an email stating that our trip was postponed out of an abundance of

caution. That seems preemptive, I thought to myself. But the scientists had understood then what I

had not, and by that weekend, everyone’s world had turned upside down with the arrival of

COVID-19. A year passed, then two.

In the summer of 2022, I finally had the opportunity to spend time on the summit with the

Mount Washington Observatory, as a volunteer and museum docent. I stayed with the crew in the

living quarters below the mountaintop weather station and spent my days cooking meals and

shadowing weather observations, filling my notebooks with everything I learned about weather

patterns from the knowledgeable observers, and sharing all of my newly-learned facts with

visitors to the Extreme Weather Museum. I also had the chance to hike to Lakes of the Clouds and

Mount Monroe on a beautiful day, experience hurricane-force winds on the summit, watch the

sunset from the highest point in all of New England, stare in wonder at the Milky Way and

surrounding stars, sip cocoa and read a book at sunrise, take a walking tour on the history of the

mountain, and play a competitive round of Settlers of Catan with the weather observers. At the

end of an adventurous week, I departed, looking forward to joining them again come winter.

On January 4th, 2023, the anticipated day finally arrived. But this time, although the trip

was on, the forecast looked dour. The higher summits forecast predicted fog with rain showers,

calm winds, and very limited visibility. There was almost no snow on the ground in the Mount

Washington Valley, the yellow grass damp and conspicuous on the ride north, and the above

freezing temperatures on the summit suggested that whatever snow they had previously had was

quickly melting. To my initial disappointment, it was neither a bluebird winter day nor a day with

an exhilarating winter storm. Still, I was about to spend my day on the summit of Mount

Washington in the winter, and how many teachers can say that? (Perhaps a few others, as I was

joined on this trip by a fellow local school teacher from Northeast Woodland Charter School and

more lucky educators will be heading up the mountain in February and March.) My first and

second grade students were especially excited. Will you REALLY be on top of Mount Washington?

they had asked me. I will be, I told them, and I’ll call you up to say hello. They had spent the

previous day making paper snowflakes and reading a book about snow.

With clear pavement at the base of the Auto Road, the drive up began in a van with

chains on the tires, before switching over to a snowcat at the two mile mark. As we climbed, the

fog began to dissipate and sunshine shone in through the skylights. It was almost too good to be

true, but sure enough, when we stopped for fresh air and a look around at 4,000 feet or so in

elevation, we had emerged from the fog and were rewarded with sweeping views of rocky slopes

and snow-filled ravines beneath patchy blue skies. Puffy cumulus clouds twisted between the

mountainous peaks, with cirrus clouds above, and stratocumulus clouds filled in the spaces beneath

like a blanket, creating an undercast. Where the road curved along the cliffside, it seemed as

though one might drive right into the clouds.

As we headed up once more - and this time, I had front row seats from the cab as

Firefighter John plowed the snow from our ice-covered path - we did, indeed, drive right into the

misty fog that wrapped around the summit itself. As the oncoming shift settled into their quarters

for the next week, MW/Obs Director of Education Brian Fitzgerald gave us newcomers a tour of

the weather station, highlighting the organization’s mission to “advance understanding of earth’s

weather and climate” and showing us handwritten records that have been documented on this site

since 1932. We giggled at the notes taken in 1935, when an observer commented in scrawled ink

on the “goofers” hiking up the mountainside.

Weather Observers/Educators Francis and Alex took us outside for an hourly weather

observation on the deck, demonstrating use of the sling psychrometer to determine relative

humidity, showing us the thermometer that tracks the ambient air temperature, and explaining how

the continual use of historic instruments adds authenticity to the patterns and trends found within

ninety years of collected weather data. Then, it was off to the tower, to check out the foggy views

from the highest point in New England and to experience winds that were gusting to forty miles

per hour out of the northwest. With windchill, it felt like seventeen degrees Fahrenheit, and I was

glad for the winter hat, mittens, and scarf that I wore in addition to my rain slicker. We learned

about how the pitot tube instrument is heated in winter and pretended to knock non-existent ice

off the anemometers using a gigantic mallet.

Our outside time was followed by a warm and hearty meal of chili and cornbread,

specially prepared by Observatory volunteers spending a week on the summit, with homemade

brownies for dessert. Then, it was back outside to explore the foggy winter wonderland on a

summit tour with Brian Fitzgerald. The Tip Top House was encased by ice and the Appalachian

Trail was as slippery as a skating rink. Luckily, we were all prepared and slipped microspikes onto

our feet so that we could take an iconic photograph with the Mount Washington summit sign. The

wind rattled the chains on the Stage Building, reminding us of the 231 miles per hour gust that

once blew across the summit and the 150 miles per hour winds that passed through as recently as

December. Though the sustained westerly winds were only reading thirty-five miles per hour

during our tour, I had some fun staggering across the observation deck with my arms outstretched

and the wind in my face.

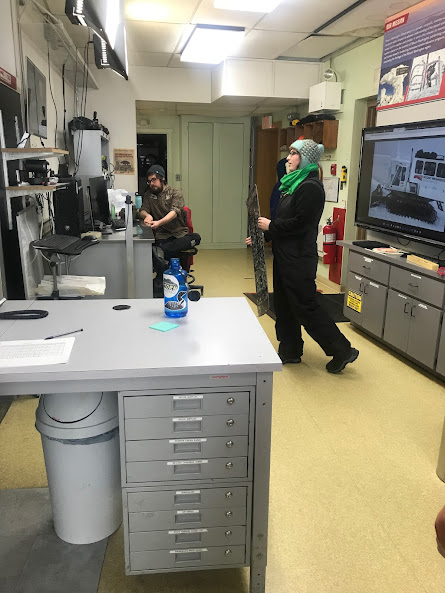

Then, we headed inside to connect with our students in the valley below. Throughout the

school year, the first and second graders have been documenting the daily weather, to answer the

comprehensive question, “What is the weather like today and how is it different from yesterday?”

On this morning, the second-grade forecaster had determined that it was “cloudy and rainy”

outside the window. I explained how, on the summit, it was also cloudy and rainy at the moment

but that the weather was different from yesterday and would be different tomorrow because of

how quickly weather moves across this landscape. We discussed how the existing ice on the summit

was because December’s snow had melted into water as it warmed then frozen into ice as it

cooled. I also shared that, by evening, the fog and rain showers were forecasted to turn to

freezing rain and sleet and snow as the temperatures dropped, and that we would probably see

some snow falling in the valley, too. Francis talked further with them about the summit conditions

and we showed them some of the equipment that the observers use to observe the temperature,

wind, precipitation, and cloud cover.

Back in the classroom, there is a book about Snowflake Bentley, a northern New Englander

who first took up-close photographs of snowflakes, and when I mentioned this to the observers,

Alex eagerly found a photograph of Bentley himself and a board depicting many of the unique

snowflake designs he had recorded. I learned that, the colder the weather, the more intricate the

snowflakes. Francis found a black felt board on which the observers catch snowflakes and we

were able to show that tool to the students.

As we continue the weather unit in the classroom, students will consider questions such as,

“How does land change and what are some things that cause it to change? What are the

different kinds of land and bodies of water?” and “What is typical weather in different parts of

the world and during different times of the year? How can the impact of weather-related hazards

be reduced?” The first and second-grade students will use science and engineering practices to

“demonstrate an understanding that wind and water can cause changes to the Earth very quickly

or very slowly; to demonstrate an understanding of typical weather conditions by organizing and

using data, making a claim about a solution that reduces impacts of weather hazards; to

demonstrate an understanding of patterns in local weather; and to demonstrate an understanding

of the purpose of weather forecasting to prepare for, and respond to, severe weather.” (SAU9

Science Curriculum)

I know that our local geography, with its mountains and valleys and lakes and

everchanging seasons, will provide an abundance of resources to which the children can connect

and expand upon their current understanding of weather. I am appreciative that, through Arctic

Wednesdays, our elementary schoolers had the opportunity to forge a connection between their

learning and a community organization who can give them an authentic and tangible look at

weather observations and forecasting in the real world and help them build a foundation as they

explore weather hazards and climate in the years to come.

As the day ended, we hurried back down the mountain to beat the incoming storm. The

students ran to the window and cheered when they saw that I was safely back at school. It almost

seemed like they had thought I was in an entirely different world and perhaps, for a little while, I

was.

Comments

Post a Comment